I. Introduction

Large-scale conflicts often cause profound economic and social disruptions, including the destruction of infrastructure, population displacement, and institutional instability. Understanding how nations achieve successful post-conflict economic recovery is a central challenge in development economics (Collier et al., 2003). While some countries suffer prolonged stagnation after conflicts, others manage to restore growth, prompting questions about what drives resilience.

The 1990–1991 Gulf War, triggered by Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, brought severe geopolitical and economic consequences. A coalition of 34 nations launched Operation Desert Storm to expel Iraqi forces. The war devastated Kuwait’s economy: infrastructure was heavily damaged, especially in the oil and gas sectors. The country’s GDP dropped sharply—from $24 billion in 1989 to $10 billion in 1991—and inflation soared to 60% (Crystal, 2016; Watson, 1992). Oil production capacity plummeted as around half of Kuwait’s oil wells were set ablaze (Limaye et al., 1992; Metz, 1994). Estimates suggest total infrastructure losses approached $100 billion, factoring asset destruction, damage to petroleum resources, and lost export revenue (Barakat & Skelton, 2014; Wilson et al., 1997).

Post-war reconstruction followed a structured five-year plan, funded mainly by oil revenues and international support (Barakat, 2005; Byman, 2000). Kuwait swiftly rebuilt its infrastructure and restored petroleum production to pre-war levels. The government also expanded social services and heightened public spending to aid recovery. Key recovery priorities included: (i) rebuilding infrastructure, (ii) restoring the petroleum sector, (iii) strengthening financial systems, (iv) enhancing security, and (v) promoting privatization and fiscal stability (Halliday, 1991; McDonnell, 2002; Metz, 1994). Restoring oil production cost between $8 and $10 billion, with firefighting efforts alone costing $1.5 billion (Husain, 1995; Warbrick, 1991). Funding came from three main sources: (i) the Kuwait Investment Authority’s sovereign resources, (ii) external debt, and (iii) reparations from Iraq via United Nations Compensation Commission sanctions. Recovery initiatives included local reinvestment requirements for foreign contractors, the purchase of $20 billion in national debt, privatization of telecommunications and gas sectors, and direct financial support to citizens (Crystal, 2016; Metz, 1994; Watson, 1992). In addition, the Food-for-Oil program allocated 30% of Iraq’s oil revenues to support Kuwait’s reconstruction (McDonnell, 2002).

Research highlights that successful post-conflict recovery hinges on financial resources, institutional resilience, and strategic governance (Holtzman et al., 1998; North, 1990). While resource-rich nations often face the “resource curse”—with challenges to diversification and democratic development (Karl, 1997; Mahdavy, 1970; Ross, 2001)—Kuwait’s experience shows how sovereign wealth and strong institutions can enable effective recovery.

Despite the wealth of descriptive accounts on Kuwait’s recovery, few studies rigorously quantify its macroeconomic impact. This paper seeks to fill that gap by applying the Synthetic Difference-in-Differences (SDD) method to assess the effects of Kuwait’s recovery program on per capita GDP.

The study addresses two research questions: (i) What were the short-term effects of Kuwait’s reconstruction program? (ii) What were the program’s long-term impacts on economic growth? Using the SDD method (Arkhangelsky et al., 2021) and data from The Maddison Project (2018), which cover 1983–2018, we construct a synthetic control group with pre-intervention trends matching those of Kuwait, allowing for robust causal inference.

Our analysis finds statistically significant, positive effects on Kuwait’s GDP per capita in both the short and long term. Robustness checks—including event study analysis and subsample analyses limited to OPEC members—support these findings. This study contributes to three streams of literature: (i) post-conflict recovery, by offering empirical evidence from a resource-rich country; (ii) resource economics, by showing how institutional strength can help overcome the resource curse; and (iii) applied methods, by demonstrating the utility of SDD for macroeconomic case studies at the country level.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section II details the data and methodology. Section III presents the main results. Section IV discusses robustness checks, and Section V concludes with policy implications.

II. Data and Methodology

The data used in this study comes from the 2020 database of The Maddison Project. The analysis period begins in 1983 to minimize the impact of the internal crisis known as Souk Al-Manakh, which affected Kuwait’s capital market in 1982 (Burney et al., 2018; Butler & Malaikah, 1992; Seznec, 1995). Kuwait launched the Recovery and Emergency Program in 1991, shortly after the end of the conflict with Iraq. The main efforts of the post-war recovery plan were concentrated in the first five years following the cessation of hostilities. Thus, the short-term analysis concludes in 1996, as most aid and investments spanned a five-year period. This timeframe also avoids the effects of the 1997 Asian financial crisis and its associated oil price shock. For the long-term perspective, the study covers the years from 1983 to 2018, with 2018 being the latest year available in the dataset. Prior to the intervention, we selected the per capita GDP variable across all available countries.

The SDD method constructs a control group that closely matches the pre-intervention trends of the treated group (Arkhangelsky et al., 2021). This model estimates the causal effect by calculating the double difference between the treated unit and its synthetic control group. To implement SDD, a balanced panel dataset with units observed over periods is required. Here, denotes the observed outcome for each unit at each period while is a binary indicator showing whether a particular observation is treated or not The process for estimating the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT) is as follows:

(^τsdid,ˆμ,ˆα,ˆβ)=argmin{N∑i=1T∑t=1(Yit−μ−αi−βt−Witτ)2^ωsdidi^λsdidt}

The estimation of the ATT is obtained using a bidirectional fixed effects regression with optimally chosen weights. This flexible approach accounts for shared aggregate temporal factors by estimating time fixed effects as well as unit-specific factors that remain constant over time through unit fixed effects Because unit fixed effects are included, SDID aligns the treated and control units based on their pre-treatment trends, rather than matching both trends and absolute levels. This allows for a consistent difference between the treatment and control groups. Unit weights are selected to ensure that treated and control units display approximately parallel trends before treatment adoption. Time weights are chosen to place greater emphasis on pre-treatment periods that most closely resemble post-treatment periods, ensuring a consistent difference between the post-treatment mean of each control unit and the weighted pre-treatment means across all controls.

III. Empirical Findings

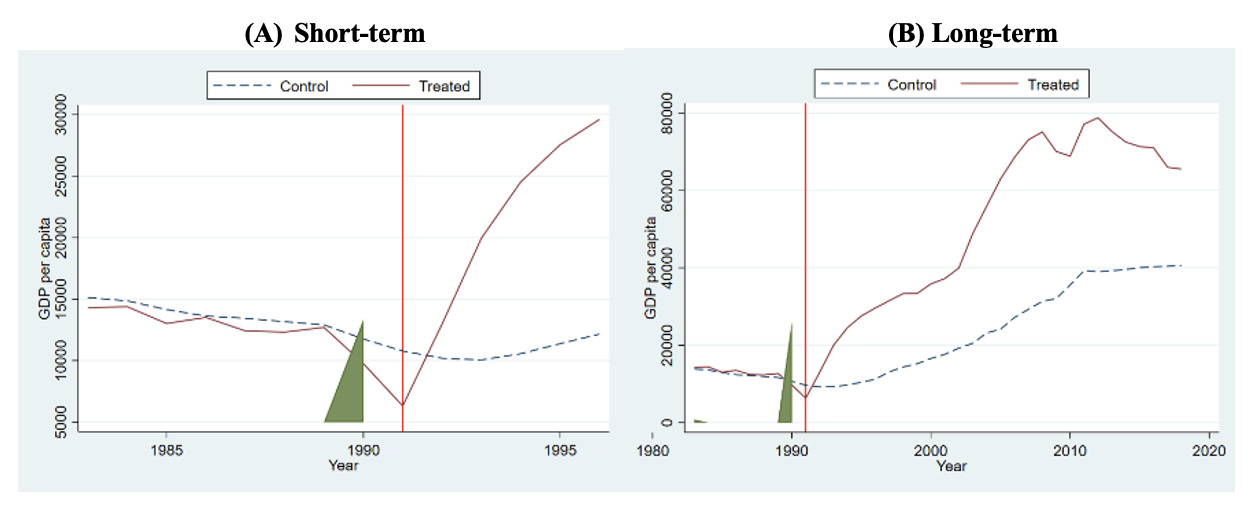

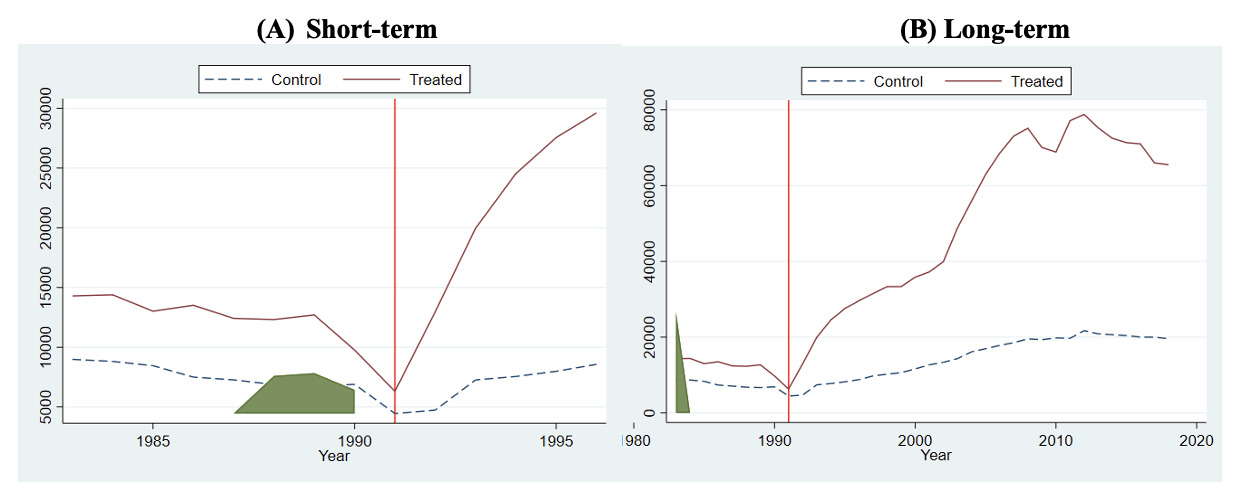

Figure 1 illustrates the treatment effects obtained using the SDD method for both the 1983–1996 and 1983–2018 periods, along with the country weights used in the estimators. The SDD estimators show an average effect of $11,301.05 (t-stat: 5.91) for the short term (2,338 records) and $27,170.03 (t-stat: 4.17) for the long term (6,012 records). The treatment effect, which began with the implementation of the post-war recovery plan in 1991, is positive and highly statistically significant (p-value < 0.001). Using the synthetic difference-in-differences estimator, we find strong evidence supporting the impact of the post-war recovery plan on Kuwait’s average income.

IV. Robustness Analysis

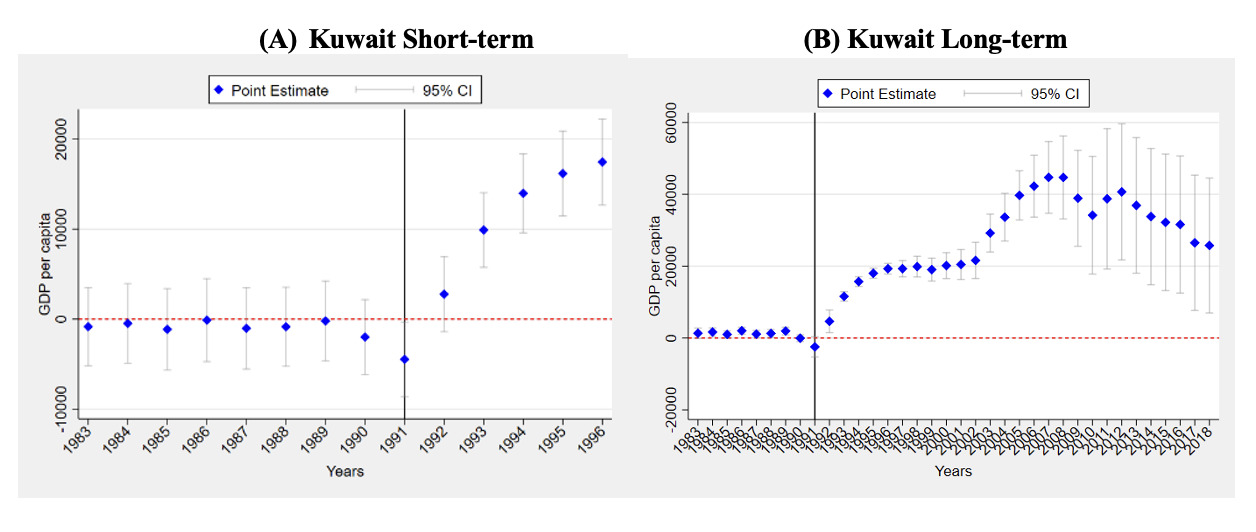

The event-study estimation framework is utilized to visualize how the treatment effects evolve over time and to identify differences between the treated and control units before the treatment is implemented. This approach helps illustrate the magnitude and timing of the treatment’s impact on the study group. We assess whether the differences between treated units and their synthetic controls shift in each period compared to pre-treatment levels, using the 95% confidence interval, which is depicted as gray horizontal lines for each period.

Figure 2 displays the treatment effects for both study periods. It is evident that short-term effects begin to manifest soon after the treatment starts and increase during the first five years of the recovery program. For the long-term, the treatment effect remains around $20,000.00 between 1995 and 2002.

Given that economies reliant on oil are generally more vulnerable to fluctuations in commodity prices, we further examine how Kuwait’s average treatment effect changes when considering only the group of OPEC countries. The SDD estimators indicate an average short-term effect of $8,345.83 (t-stat: 5.93) based on 182 records, and a long-term effect of $30,923.16 (t-stat: 2.69) based on 468 records. These results remain consistent with the main findings. We conclude that the choice of comparison sample does not significantly alter the estimated average treatment effect, reaffirming the positive impact of Kuwait’s economic recovery program.

Once again, using the synthetic difference-in-differences estimator within this subsample, we do not reject the hypothesis that the post-war recovery plan positively affected Kuwait’s average income.

V. Conclusion

This study confirms the positive impact of Kuwait’s post-Gulf War economic recovery program on per capita GDP. Using data from The Maddison Project 2020 and applying the synthetic difference-in-differences method, this research highlights the significant progress achieved through Kuwait’s recovery efforts. The notable short-term effect, averaging $11,301.05, demonstrates the immediate benefits of the economic initiatives. Furthermore, the long-term effect—an average per capita income increase of $27,170.03—shows the enduring impact of these policies. Robustness checks further strengthen the credibility of these results.

The study contributes to our understanding of post-conflict economic trajectories and illustrates how targeted recovery strategies can foster sustained growth and stability in economies affected by conflict. Overall, the findings empirically substantiate the effectiveness of Kuwait’s post-Gulf War recovery program, underscoring its role in revitalizing the economy and improving citizens’ well-being through sustained per capita GDP growth.

The implications for policy are significant. The success of Kuwait’s recovery program suggests that institutional quality is a key determinant of positive outcomes in such initiatives, as strong institutions foster stability and safeguard economic assets (Acemoglu et al., 2005). While Kuwait’s post-war recovery was centrally coordinated by the state, it is important to note that this study only examines GDP, without considering income distribution or productivity. Future research should extend the analysis to cover employment, capital accumulation, and financial development to provide a more comprehensive perspective.