I. Introduction

Despite extensive research on exchange rate movements (see Korley & Giouvris, 2021), current models—such as monetary and portfolio balance models—are widely viewed as insufficient for delivering robust and reliable forecasts. A significant gap in these frameworks is their failure to account for economic policy uncertainty (EPU) as a potential driver of exchange rate volatility (see Abid, 2020; Adjei & Adjei, 2017; Baker et al., 2016). While debate persists over whether ambiguity or uncertainty should theoretically impact price volatility, it is undeniable that expectations influence both supply and demand. Thus, elevated uncertainty about government policy and its implementation is likely to intensify unpredictability in exchange rate movements. For example, EPU can affect export and import levels, thereby shifting the demand for foreign currency and influencing exchange rates. Furthermore, changes in interest rate policy can impact borrowers’ decisions between domestic and foreign currency loans, shaping exchange rate dynamics. This theoretical link between economic policy uncertainty and exchange rates has motivated increasing empirical investigation into the role of uncertainty as a new source of exchange rate volatility (see Aftab et al., 2024; Bush & Noria, 2021; Liming et al., 2020; Zhou & Zhang, 2023). However, most of these studies rely on the global economic policy uncertainty (GEPU) indices derived from newspaper articles compiled by Baker et al. (2016). This dependence raises questions about the generalizability of findings, especially for African economies, which are often not adequately represented in indices such as GEPU. Consequently, the primary aim of this study is to determine whether exchange rate volatility in the context of policy uncertainty is more heavily influenced by global or domestic sources of EPU. To address this, the study contributes to the literature on the EPU–exchange rate volatility nexus in several key ways.

First, measuring economic policy uncertainty (EPU) accurately remains a complex challenge due to the multitude of channels through which governments interact with markets. The Global Economic Policy Uncertainty (GEPU) index, developed by Baker et al. (2016), is a pivotal tool in this area. Despite its global relevance, the GEPU index’s lack of explicit coverage for African countries limits its applicability to African economies. In response, Salisu et al. (2023) developed an Africa-focused EPU, specifically for Nigeria. This index reflects the unique economic and policy environment of Nigeria, a major actor in Africa’s economy. The Nigerian Economic Policy Uncertainty (NEPU) index is primarily centered on domestic factors in an economy that is nonetheless highly sensitive to external shocks, prompting a reassessment of the hypothesis that EPU drives exchange rate volatility.

Building on this background, the first contribution of the current study is to investigate the comparative effects of EPU—both global and domestic—on the volatility dynamics of Nigeria’s exchange rate. The second contribution moves beyond traditional impact analysis, testing which type of EPU, global or domestic, is more significant for out-of-sample forecasts of exchange rate volatility. Third, earlier studies using the monthly EPU indices from Baker et al. (2016) to analyze month-to-month exchange rate volatility may have captured broad trends in policy uncertainty, but risk overlooking important short-term fluctuations. To address this, we employ a GARCH-MIDAS framework. This approach allows us to leverage daily exchange rate data and monthly EPU data at their respective frequencies, capturing detailed and dynamic interactions without loss of information.

After this introduction, the remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section II details the data and methodology; Section III presents and discusses the empirical findings; and Section IV concludes the study.

II. Data and Methodology

A. Data

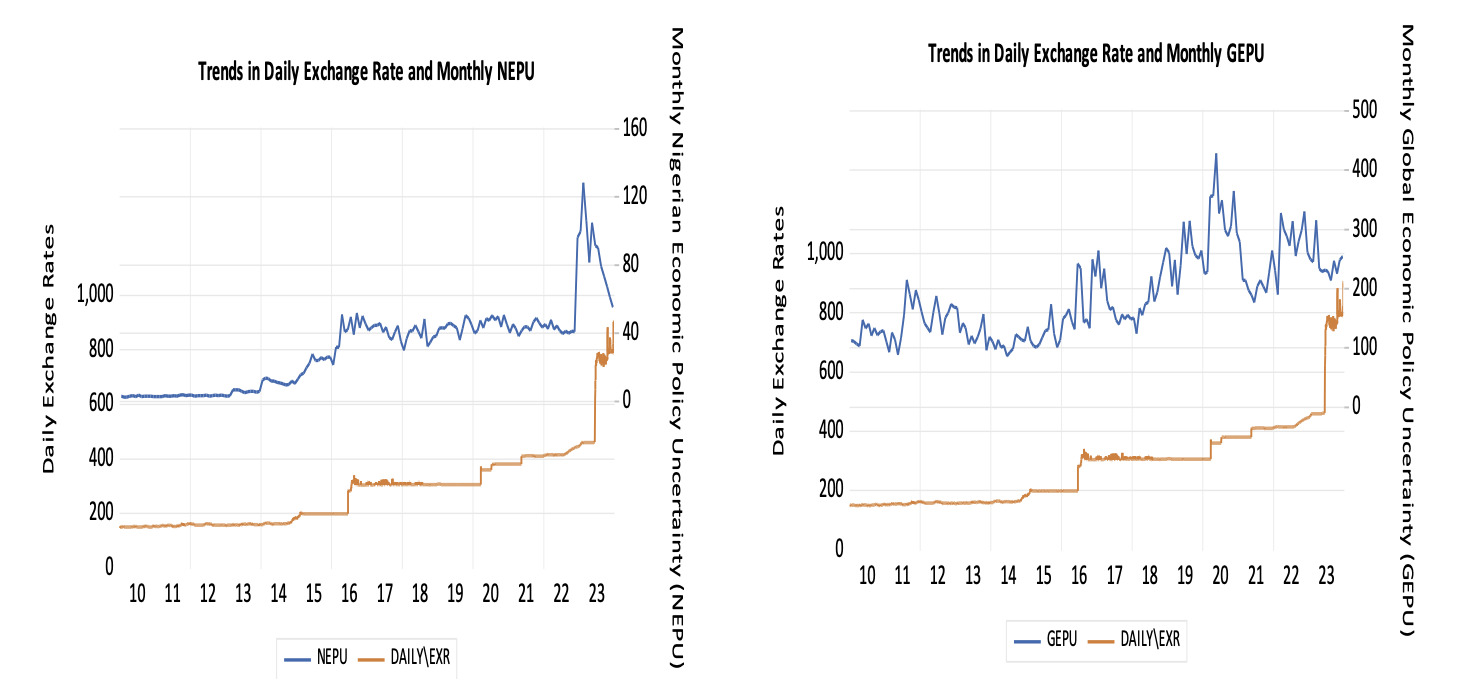

The dataset spans from January 2012 to December 2023, with the availability of the African NEPU index determining this timeframe. Daily Nigerian exchange rates against the USD were obtained from investing.com, and both stock prices and the NEPU index are available daily. By contrast, the GEPU index is only provided monthly; therefore, both indices are analyzed at a monthly frequency for consistency. During the estimation process, all series are represented as the first difference of their natural logarithms to enable interpretation in percentiles. The GEPU index methodology follows Baker et al. (2016)[1], while the NEPU index is based on Salisu et al. (2023)[2]. This study focuses on the NEPU—Africa’s version of the EPU index—to establish the beginning and end periods. For comparability, both the NEPU and GEPU are utilized at monthly frequencies, and all series are expressed as the first difference of their natural logarithms during estimation.

Presented in Table 1 are additional statistics of interest, including the F-statistic from an autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity (ARCH) test and the Q-statistic/Q-square-statistic from the Ljung-Box autocorrelation test. These tests are conducted across three different lag lengths (k = 5 and k = 10) for consistency and robustness. The results provide substantial evidence of conditional heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation in the exchange rate series. Together with other factors, this supports the appropriateness of our chosen estimation technique in the subsequent section.

Furthermore, Figure 1 offers visual representations of potential co-movements between the exchange rate and EPU. A preliminary review of the figure suggests a strong positive correlation between the exchange rate and the EPU index—particularly from the domestic perspective—providing a compelling basis for further investigation.

B. Methodology

The exchange rate and EPU data are observed at different frequencies—the EPU is available monthly, while exchange rate data is collected daily. To address this disparity, we employ the GARCH-MIDAS model, introduced by Engle et al. (2013), which is specifically designed to integrate variables sampled at different intervals within a unified framework. This approach allows us to preserve the intrinsic characteristics of each variable and avoids potential information loss that can occur when data is forced into a single frequency. Consequently, GARCH-MIDAS is well suited to our goal of assessing the distinct predictive power of NEPU and GEPU in forecasting exchange rate volatility.

eri,t=μ+√τt×hi,tεi,t,εi,t|Φi−1,t∼N(0,1),∀i=1,...,Nt

hi,t=(1−α−β)+(eri−1,t−μ)2τi+βhi−1,t

τ(rω)i=m(rω)+θ(rω)K∑k=1ϕk(ω1,ω1,)X(rω)i−k

Equations (1), (2) and (3) lay out the structure of the GARCH-MIDAS model used in this study. Specifically, Equation (2) is the mean equation, while Equations (2) and (3) capture the conditional variance components—short-run and long-run, respectively. In Equation (1), the parameter represents the average (unconditional mean) of the exchange rate return series, and denotes the short-run volatility component, which follows a GARCH(1,1) process. The parameters and correspond to the ARCH and GARCH terms, respectively. These parameters are constrained to be non-negative and and their sum must be less than one to ensure model stability.

The long-run component, incorporates exogenous factors—such as the EPU indices or realized volatility—and is constructed by extending the monthly value across all days within that month. In Equation (3), the parameter, results from the application of a rolling-window approach, allowing the long-run trend to update monthly. The parameter represents the intercept of the long-run component.

Of particular interest is the slope coefficient, which measures the predictive influence of the EPU series on exchange rate volatility. Finally, the weights, are non-negative and are designed to sum to one, ensuring proper identification of the model’s parameters. Together, these elements enable the model to flexibly and accurately capture both short-term and long-term volatility dynamics while integrating explanatory variables observed at different frequencies.`

III. Empirical Result

The primary focus of this study is to assess whether uncertainty arising from changes in economic policy intensifies exchange rate volatility, and whether this effect differs between domestic and global sources of uncertainty. The key parameter of interest is the slope coefficient which, as presented in Table 2, is statistically significant not only for realized volatility (RV) but also for external factors (GEPU and NEPU). This finding indicates that the null hypothesis of no predictability is rejected for both RV and the two alternative dimensions of EPU. Notably, while the coefficient is positive for RV, it suggests that larger fluctuations in RV lead to increased exchange rate volatility and the effect is even greater when NEPU and GEPU are the underlying sources of volatility. These results provide robust evidence that EPU acts as an amplifier of exchange rate volatility, highlighting that higher EPU differentials are associated with increased foreign exchange market activity. Furthermore, our analysis demonstrates that the volatility-inducing effect of EPU is more pronounced for NEPU than for GEPU.

Furthermore, a comparison of the forecast performance of alternative EPU-based GARCH-MIDAS predictive models, using the Harvey et al. (1997) out-of-sample forecast evaluation approach, shows that the GARCH-MIDAS model incorporating NEPU outperforms GEPU in predicting exchange rate volatility. This result remains consistent across various sample sizes and forecast horizons. The analysis indicates that the effectiveness of EPU in forecasting exchange rate volatility depends on whether domestic or global EPU dynamics are considered. The consistency of these results supports the dependability of the research outcomes.

IV. Conclusion

To determine which dimensions of Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) significantly influence exchange rate volatility dynamics, we employ the GARCH-MIDAS model, which accommodates variables observed at different frequencies. Our findings reveal that both Global Economic Policy Uncertainty (GEPU) and National Economic Policy Uncertainty (NEPU) contribute to exchange rate volatility. However, NEPU exerts a comparatively greater impact than GEPU. Moreover, we demonstrate that NEPU’s predictive power regarding exchange rate volatility is more pronounced when compared to GEPU. This suggests that policymakers should prioritize reducing domestic risks to enhance currency stability.

See https://www.policyuncertainty.com/ for the GEPU data

See https://epuindexng.com/ for the NEPU data