I. Introduction

Climate-related shocks are increasingly influencing macroeconomic dynamics, compelling central banks to reconsider the role of monetary policy in managing climate uncertainty. These challenges arise from both physical risks (such as extreme weather events disrupting labour and supply chains) and transition risks (for instance, policy shifts towards low-carbon economies generating inflation and structural adjustments). Such risks complicate both price stability and financial stability, necessitating a reevaluation of traditional monetary frameworks.

The literature highlights two core challenges: maintaining price stability and addressing climate risks while adhering to central bank mandates. Hansen (2022) cautions against expanding the scope of monetary policy without solid empirical evidence, as this may undermine institutional credibility. While advanced DSGE models now incorporate climate-related factors like carbon taxes and renewable energy investments, conventional models often struggle to fully capture these complexities.

Drudi et al. (2021) note that climate change weakens the transmission of monetary policy and complicates the identification of economic shocks. Studies such as Thakoor and Kara (2023) suggest modified policy rules to address climate-induced productivity shocks, while others propose integrating climate mitigation objectives into monetary targets—though this approach may conflict with central bank mandates.

Existing research largely overlooks the effect of climate risks on monetary policy in developing economies such as Nigeria, where vulnerabilities are especially pronounced. Prior use of Bayesian DSGE models in Africa has typically failed to include climate variables, resulting in significant gaps in understanding (Nkang et al., 2022; Obioma et al., 2022). This study addresses these gaps by applying a Bayesian DSGE framework to evaluate monetary policy effectiveness under climate uncertainty. It integrates climate risks into a probabilistic structure, offering insights into policy tools like green quantitative easing and targeted refinancing.

The findings indicate that climate shocks substantially weaken the effectiveness of monetary policy, as interest rates tend to respond negatively. These results carry important policy implications, supporting the design of resilient strategies that align climate mitigation with economic stability.

This research advances the existing literature by incorporating climate risks into a Bayesian DSGE framework, thereby addressing a significant gap in African macroeconomic modeling and providing new perspectives on the impact of climate shocks on the effectiveness of monetary policy. Furthermore, it examines the potential of climate-aligned policy instruments to enhance economic resilience.

The reminder of the paper is organized as follows. Section II details the methodology, Section III presents the results, and Section IV offers conclusions along with policy recommendations.

II. Methodology

This study employs a Bayesian DSGE framework for its analytical robustness and flexibility (Del Negro et al., 2015), integrating external sector dynamics and climate change variables in line with Woodford’s (2003) model. The aim is to assess how monetary policy, productivity, demand, and climate shocks affect output and inflation in Nigeria’s small open economy. Key structural features include household, firm, and government optimization, as well as forward-looking price-setting mechanisms (Nkang et al., 2022; Salisu et al., 2022).

The baseline linear model from Woodford (2003) is specified as follows:

1=βEt(XtXt+11GtRtΠt+1)

(Πt−Π)+1ϕ=ϕXt+βEt(Πt+1−Π)

RtR=(ΠtΠ)1βUt

where is a state variable that captures

A. Baseline model

The linearized model in Equations (4) – (8) describes the baseline Woodford’s model.

πt=[βEt(πt+1)+κxt]

xt=Et(xt+1)−{rt−Et(πt+1)−gt}

rt=1βπt+ut

ut+1=ρuut+ϵt+1

gt+1=ρggt+ξt+1

The baseline model describes how deviations in inflation and interest rates from their steady states are determined. The New Keynesian Phillips Curve (Equation 4) captures forward-looking price-setting behavior. The Euler equation (Equation 5) links consumer decisions to the output gap. The Taylor rule (Equation 6) defines monetary policy, while Equations (7) and (8) represent monetary policy and productivity shocks as AR(1) processes.

B. Estimation procedure

The linear DSGE model, which incorporates climate change in its second version, was estimated using a Bayesian approach with the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm and Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations. Initial estimation encountered autocorrelation issues; these were resolved by re-estimating with a block option and increasing the number of iterations to 67,000, which produced interpretable results.

The Bayesian estimation procedure for the DSGE model begins by specifying prior distributions that reflect existing knowledge before the data are taken into account. In this study, priors were chosen based on theoretical considerations, institutional insights, and empirical literature. Specifically, the priors were informed by the works of Woodford (2003), Obioma et al. (2022), and Nkang et al. (2022) (see Table 1).

III. Main Findings

Table 2 presents the structural parameters, persistence coefficients, and the acceptance and maximum efficiency parameters for both the baseline and extended models. The Bayesian linear DSGE model estimates, which address inflation and monetary policy dynamics in Nigeria, reveal significant findings: inflation coefficients slightly above unity (1.02 and 1.01 for the baseline and extended models, respectively) reflect the Central Bank of Nigeria’s proactive inflation-targeting approach, in line with the Taylor Rule. Expected inflation is a strong determinant of current inflation, demonstrating the forward-looking nature of inflationary dynamics. The output gap’s effect on inflation is more pronounced in the extended model, underscoring the influence of external factors such as exchange rates and crude oil prices. Persistence coefficients indicate that production or technology shocks have the most enduring impacts, while higher acceptance rates and efficiency values confirm the extended model’s robustness in capturing Nigeria’s economic complexities. These results are consistent with the Taylor Rule, which emphasizes the proportional response of interest rates to deviations in inflation, and align with empirical findings from Obioma et al. (2022) and Nkang et al. (2022).

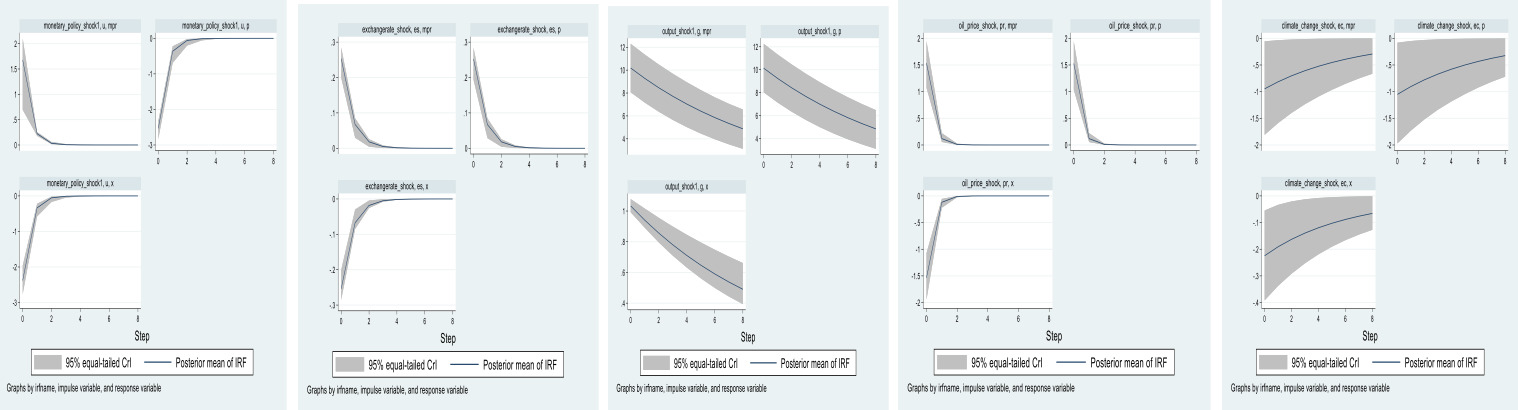

Figure A presented in the appendix and Table 3 highlight the effects of monetary policy and output shocks in Nigeria. A 1% monetary policy shock initially widens the output gap (-13.68%) and reduces inflation (-13.99%), demonstrating the contractionary impact of tighter policy. Conversely, a 1% output shock narrows the gap (0.21%) and pushes inflation higher (1.09%) due to supply-side pressures. Interest rates respond positively to both shocks (0.01% and 1.11%), underscoring the Central Bank’s stabilising role in accordance with the Taylor Rule and theoretical expectations. All responses remain statistically significant within the 95% confidence interval throughout the forecast horizon. These findings support those of Obioma et al. (2022) and Nkang et al. (2022), who also observed that output gap and inflation react negatively and positively, respectively, to monetary policy shocks in Nigeria.

Figure B presented in the appendix and Table 4 present the responses of the output gap, inflation, and interest rates to monetary policy, nominal effective exchange rate, output/technology, crude oil price, and climate change shocks in Nigeria. In response to monetary policy shocks, output and inflation initially declined by -2.38% and -2.54%, respectively, while interest rates rose by 1.68%, consistent with the Taylor Rule. These effects highlight the contractionary impact of monetary policy on output and inflation, as well as the central bank’s counter-cyclical adjustments. The results further suggest that incorporating climate variables reduces the effectiveness of monetary policy in controlling inflation, indicating the uncertainty introduced by climate change. Inflation’s initial response to monetary tightening decreases from -13.99% to -2.54%, underscoring the need to integrate climate mitigation into policy frameworks.

Inflation and interest rates both increase by 0.25% in response to nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) shocks, while the output gap contracts by 0.25%. This result highlights the inflationary pressures that accompany exchange rate depreciation and the subsequent rise in production costs in Nigeria’s import-dependent economy.

When output or technology shocks arise, a 1% positive shock leads to increases across all metrics: the output gap expands by 1.03%, inflation jumps by 10.14%, and interest rates rise by 10.19%. These pronounced inflationary effects—aggravated by climate change—underscore the importance of structural and technological improvements to stabilize supply-side disruptions.

Crude oil price shocks, meanwhile, significantly impact the economy, raising both inflation and interest rates by 1.53% each, and widening the output gap. This underscores how fluctuations in oil prices drive inflation and prompt policy tightening in Nigeria’s oil-dependent economy, in line with the New Keynesian Phillips Curve, which connects inflation, output gaps, and supply-side factors. The muted inflation response under climate uncertainty further emphasizes the need to address structural and external supply challenges. These outcomes are consistent with the findings of Obioma et al. (2022) and Nkang et al. (2022), who also report that crude oil price shocks fuel inflation, induce monetary tightening, and expand the output gap in Nigeria.

In contrast, climate change shocks result in declines across all three variables: the output gap decreases by 0.22%, inflation drops by 1.05%, and interest rates fall by 0.95%. This demonstrates the role of climate change in widening output gaps and diminishing the effectiveness of monetary policy, potentially leading to deflationary pressures due to weakened aggregate demand, especially in informal sectors and climate-sensitive industries.

Additionally, the downward movement in interest rates suggests that monetary authorities may adopt a more accommodative policy stance in the face of climate-induced economic shocks, aiming to stimulate demand and cushion the broader economy. These findings highlight the necessity of integrating climate considerations into Nigeria’s monetary and fiscal policy frameworks to address the complex economic dynamics brought about by climate shocks.

IV. Conclusion

This study examines the effectiveness of monetary policy under climate uncertainty in Nigeria using a linear Bayesian Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) model. Data from the CBN Statistical Bulletin (2023) and International Financial Statistics (IFS) covering 2000Q1–2024Q2 were analyzed, building on Woodford’s (2003) closed-economy framework, which was modified to incorporate nominal exchange rate, crude oil price, and climate change shocks.

The baseline model demonstrates that inflation responds positively and significantly to monetary policy and negatively to output/technology shocks. When external and climate-related shocks are included, the inflationary impact of these disturbances intensifies, underscoring the amplifying effect of climate uncertainty on economic disruptions. These findings indicate that conventional monetary policy measures become less effective in the face of climate uncertainty, highlighting the need to integrate climate mitigation strategies into monetary frameworks to maintain macroeconomic stability amid increasing climate-related challenges.

Data and Replication Statement

Data used in this study can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon request. The codes utilized in the study are provided for reference, and the data sources include CBN and IFS.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Aminu Umaru: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. Ado Nuhu: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Validation, Resources, Visualization.

Funding Acquisition

None.