I. Introduction

Meat consumption is affected by diet, standard of living, amount of animal production, consumer-based pricing, gross domestic product (GDP) shocks and uncertainty in macro-economic activity which lead to high production costs as well as high output prices when compared with other commodities. The increasing demand for meat correlates with a rise in income and a change in consumption of food habits, brought on by urbanization which encourages increased demand for protein from animal sources. Urbanization will gain momentum in the coming decade. The rising population has boosted livestock expansion, with about 340 million tonnes of meat being extracted from approximately 80 billion animals for human consumption in each year (Ritchie & Roser, 2017). Huang & David (1993) show that urbanization decreased the demand for cereal grains in high-income nations. Some studies suggest that with an increase in urbanization comes an increase in food demand as there is a high demand for food in urban areas (Mendez & Popkin, 2004; Popkin, 1999). According to projections made by FAO in 2006, meat consumption will quadruple by 2050 as a result of rising income in developing nations and economic expansion (Delgado, 2003). Over the last 20 years, emerging economies have witnessed a livestock revolution owing to an increase in meat consumption, particularly meat from poultry (Delgado, 2003). A study on China and India by Stage et al. (2010) reveals the impact of urbanization on food demand and argues that individuals in urban regions would likely have more money which could account for why they spend more on food. However, attention must be paid to the effects of rapidly expanding animal production in close proximity to urban areas on the environment, nutrition, and public health (Delgado et al., 2001).

There is ample amount of theoretical and empirical models that examines the relationship between nutrition and economic growth. Most important among them are the exogenous and endogenous growth theories. The endogenous model, apart from “Capital”, contains a new category called “Human Capital”. Romer (1986) and Lucas (1988) suggest that high human capital promotes faster growth. Therefore, both models present varying arguments on the long-term effects of nutrition on economic growth. Hence, labourers’ with improved nutrition will get trained much faster than those who are not getting proper nutrition. In this case, the diminishing returns mentioned in an overly restrictive definition of capital may not exist. The balanced path would experience growth, raising the rate of long-term economic growth.

This study will contribute to the literature on nutrition, meat consumption and food system transformation across countries with different levels of urbanization and could provide important insights on how this could drive rural transformation through linkages to vending, processing and production. The research will also contribute to policy formulation regarding sustainable urbanization and nutrition in future.

The rest of the paper shows the data and empirical methods, followed by the results, conclusion, and policy implications.

II. Data and Empirical Method

To study the impact of meat consumption on other variables we formed panels and collected data from the Food and Agriculture Organization and World bank. All eight variables utilized in this study are: meat consumption (LnMC) as an outcome variable, live animals (LnLA), meat production (LnMP), major livestock (LnML), Gross Fixed Capital (LnGFC), Gross Saving (LnGS), Inflation (LnI), and Urbanization (LnU) as an Explanatory variable. Here, we have used a simple ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, panel quantile regression and system and dynamic generalized method of moments (GMM).

A. Estimation Methods

The study shows the impact of live animals, meat production, major livestock, Gross Fixed Capital, Gross Saving, inflation, and urbanization on meat consumption in South Asian countries using three methods. Our model includes four cases, country effect, time effect, country and time effects, and with no fixed effect. Quantile regression is employed to analyze the complete sample while giving each quantile a distinct weight and estimating the effects of independent variables on particular quantiles of an outcome variable, and thus overcoming any sample selection bias (Heckman, 1979). The GMM is one of the econometric methods to address the issue of endogeneity (Bond, 1991). This method will take care of the issue of endogeneity with the help of lagged values as an instrument and by converting the data through differences in time.

We specify one baseline model:

LnMCi,t=β0+β1 . LnLAi,t+β2 . LnMPi,t+β3 . LnMLi,t +β4 . LnGFCi,t+β5 . LnGSi,t +β6 . LnIi,t+β7 . LnUi,t+ϵi+ϵt+ϵi,t

and are given by Country and Time respectively, in Equation 1, where is an error term. Using meat consumption as the main dependent variable, we examine the correlation among all the variables. The possible issues of heteroskedasticity, endogeneity, control serial correlation, and heterogeneity are addressed by this empirical dynamic panel method.

III. Results and Discussion

An econometric OLS, Panel Quantile, and GMM method is used to investigate the relationship between meat consumption and some specific independent variables in South Asian countries. Table 1 displays the results of the OLS model.

A. Simple Regression Results

Table 1 displays the results of a simple linear regression taking all four conditions into consideration. The results show that a 1% increase in urbanization will increase meat consumption by 0.152%, 0.124%, 0.01% and 0.124%, implying that Urbanization has a direct and positive impact on meat consumption in South Asian countries. This result is in line with the study conducted by Benson (2004) which shows economic growth to be an important variable for reduction in malnutrition as well as an important one for improvement in nutrition, while per capita income is an important variable for improvement in nutrition (Ogundari & Abdulai, 2013). Similarly, 1% increase in meat production will increase meat consumption by 0.947% with country and time effect, 0.895% with country effect and 0.947% with time effect, which implies meat production in South Asian countries has a direct and positive impact on meat consumption. As a result, 1% increase in inflation will increase meat consumption by 0.004% with country and time effect, 0.008% with country effect and 0.004% with time effect, which implies that with time and country effect, inflation will positively impact meat consumption. Previous studies by Stubbs (1980) shows that with an increase in inflation, there will be an increase in consumption of nutritional diet as people will stop investing in junk food items.

B. Panel quantile regression results

Table 2 presents the results of the Panel Quantile Regression. The results show that Urbanization has a significant and positive impact on meat consumption. At the 25, 50, 75 and 90 Quantiles, the coefficients of Urbanization are 0.244%, 0.255%, 0.085% and 0.053% respectively. It shows that for every 1% increase in Urbanization, the rate of meat consumption in the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th quantiles increases by 0.244%, 0.255%, 0.085% and 0.053% respectively. These results follow the study which implemented the GMM model, and suggest that nutritional improvement is dependent on economic growth (Ogundari & Aromolaran, 2017). Similarly, Investment has a positive impact on meat consumption at the 25th and 50th Quantiles. Our findings indicate that for every 1% increase in Investment, the rate of meat consumption will increase by 0.034% and 0.013% at the 25 and 50 Quantiles respectively.

C. Generalized methods of moment dynamic and systematic

Table 3 shows the generalized method of moments which contains the coefficient and standard error of outcome as well as explanatory variables. The results of the Sargan and Hansen test are robust and significant and the coefficient of Urbanization is positive in the dynamic test which shows that a 1% increase in Urbanization will increase meat consumption by 0.016%. These results are in line with Rae (1998) which argues that in six East Asian countries, foods made from animal products are more frequently consumed in urban areas. Similarly, the coefficient of meat production and inflation is positive which is reflected in a 1% increase in meat production and inflation increasing the meat consumption by 0.799% and 0.009%, respectively. Conversely, the coefficient of Investment is negative, showing that a 1% increase in Investment will decrease meat consumption by 0.009%. A similar study by Betru & Kawashima (2009) on Ethiopia shows that urbanization and income will positively and significantly impact consumption patterns of meat.

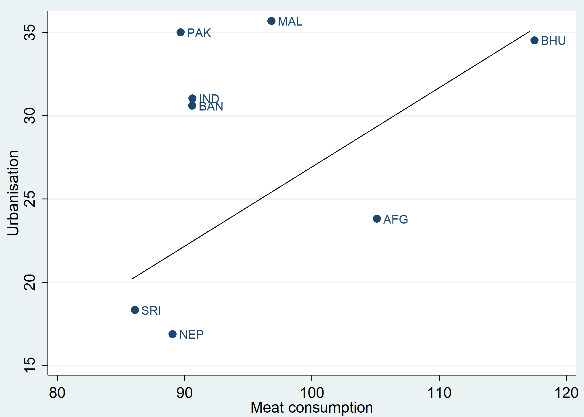

Figure 1 in the Appendix shows that with an increase in urbanization there will be an increase in consumption of meat products. Malnutrition decreases the economic growth of poor countries (Correa & Cummins, 1970). Increase in caloric intake will increase productivity and therefore meat consumption will rise.

IV. Conclusion

This paper examines the relationship between urbanization and meat consumption. By applying OLS, Panel and GMM techniques, the results show that urbanization has a positive significant effect on meat consumption, indicating that there are a variety of reasons why urbanization can result in changes in food consumption patterns. Gross capital formation also has a positive impact on meat consumption, which indicates with the increase in country’s investments there will be an increase in consumption. This study could be useful to policymakers in addressing three major policy issues. Firstly, it aids in the identification of the best policy initiatives for enhancing the nutritional standards of individuals and households. Secondly, it helps in developing different food subsidy plans that the government could employ. Thirdly, doing sectoral and macroeconomic policy studies requires some knowledge of food demand dynamics.